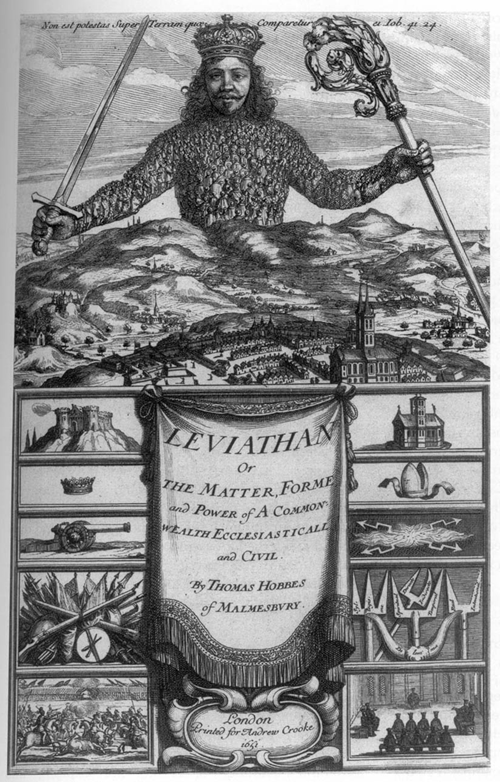

With black blocs and yellow vests as their starting point, Maxime Boidy and Julia Marchand evoke the representation of bodies or crowds in political iconography, from James Ensor to Jeremy Deller, in the pervasive shadow of Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan.

Published on Switch on Paper

Julia Marchand: A sociologist by training, you now define yourself as a researcher in “Visual Studies”, a discipline better known in the English-speaking academic world. Your thesis, defended in 2014, focuses on the visual culture and political iconography of the black bloc, which you define as a “visual terrain of the global1 ». How do you analyse the black bloc as a sociologist and as a visual studies researcher?

Maxime Boidy: Although their intellectual history is older, Anglo-American Visual Studies were structured during the 1980s and 1990s around a “pictorial turn”, echoing in particular the linguistic turn described two decades earlier by the philosopher Richard Rorty2. Henceforth, it was the image, and no longer language, that constituted the primary framework of intelligibility of our societies, the foundation of our knowledge, our forms of communication, and even our economic and political conditions.

The revolutionary impact of this “pictorial turn” didn’t actually interest me much. On the other hand, I have developed a curiosity for one of its central theses: that this pictorial turn occurred simultaneously in scientific knowledge and in the context of daily life, the two going hand in hand. In the academic learning, particularly in political philosophy and the social sciences, visibility has indeed become an abundant, polysemous term, which today serves to redefine both public space and human subjectivity. In “ordinary” discourse, or quite simply, in everyday life, entrepreneurial communication or militant discourse, the notions of visibility or invisibility are increasingly present. Entering professional life, or simply existing and counting in the eyes of others, is now expressed through this vocabulary. It is a very important recent phenomenon3.

This is where black bloc comes in. It refers to the urban demonstration tactic of marching together, wearing masks and black clothing to stop the police from identifying the activists. This tactic, which appeared in the 1980s in West Germany, has been steadily expanding throughout the world, within the most diverse anarchist and protest circles, to the point of becoming a “visual terrain of the global”, an expression by which I have attempted to account for its global expansion from the original political roots of the black bloc, prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall. What interested me was that its emergence coincided exactly with the periodization of the “pictorial turn”. On the other hand, the global expansion of the uses of black bloc has been marked by numerous activist discourses on visibility – the most famous, not only in France, but elsewhere in the world, being that of the aptly named “Invisible Committee”.

My thesis was theoretical. One could say that it focused less on black bloc than on the difficulties, even the impossibility of accounting for it based on current academic disciplinary knowledge. Artistic approaches seem to me to be better equipped than social sciences, given the need to pay real attention to aesthetics. Sociology and political science work by analysing a previously delimited “terrain”, whether it is a corpus of events or a social movement as a whole, such as the “Yellow Vests” today. In terms of method, these disciplines proceed by questioning the actors, producing statistical data from this, trying to compare certain practices with other “repertoires of action”: this is what, for sociologists, designates wearing a yellow vest to demonstrate and mobilize collectively. For my part, I have sought to make other, more unexpected comparisons to gain a new understanding of the phenomenon. In particular, I wanted to show that, far from being a simple militant practice, the black bloc materializes our conditions of contemporary political visibility. It is an “epistemological image”, i.e. an image that is both literal and metaphorical and illustrates the way we understand vision. It pits anonymity against celebrity worship, camouflage against generalized video surveillance, the standardization clothing against the omnipresence of fashion advertising in urban areas, etc. I borrowed the idea from the American theorist Jonathan Crary, who applied it to a completely different visual object: the camera obscura in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A technical device for painters, the camera obscura was also at that time a metaphor for understanding, which was widespread among philosophers. The black bloc now has “mixed” status similar to the camera obscura of yesterday, namely that of “an epistemological figure within a discursive order and an object within an arrangement of cultural practices4”. In short, sociologists compare the black bloc to other forms of activism and demonstration. For my part, I compare it to other ways of seeing and representing.

Full interview can be read here